By Matthew Everett (Contact)

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

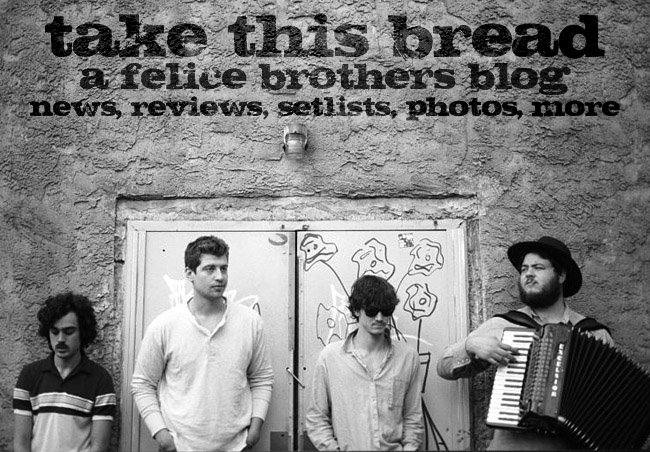

The Felice Brothers

James Felice isn’t usually the voice of the Felice Brothers. When the accordion player has just woken up in the middle of the afternoon in the back of the band’s RV somewhere in the middle of Kentucky, he’s even less suited to interviews. In the middle of a phone conversation, he’s likely to set down the phone and take a good long, steady leak.

“Could you hear that, man? Sorry,” he says.

Felice’s discombobulation is understandable, though, considering what the last few months have been like for his band. The five-piece group—the three real Felice brothers, James, singer/guitarist/songwriter Ian, and drummer Simone, along with a pair of their childhood friends known only as Christmas and Farley—seems to be on the verge of national exposure with the release of its new album, Yonder Is the Clock. They’re tangentially based in New York, where they got their start playing together at subway stations near Greenwich Village, but their home now is essentially the Winnebago.

“It’s been renovated inside with a bunch of bunk beds,” Felice says. “We used to just tour in a bus, so this is a lot better.”

The group’s new CD has gotten positive, sometimes glowing reviews from Entertainment Weekly, Spin, and The New York Times. Critics have been nearly unanimous in comparing the disc to The Basement Tapes, the eccentric 1967 collaboration between Bob Dylan and the Band that was released in 1975. Part of that comparison comes from the Felice Brothers’ roots in upstate New York, similar to the location of the old farmhouse where The Basement Tapes were recorded. Part of it is that Ian Felice sings in a nasal drawl similar to the youthful Dylan. Mostly it’s that Yonder Is the Clock has the same kind of ramshackle, homespun charm of the Dylan/Band project. Like The Basement Tapes, Yonder is nostalgic but not remotely authentic; the Felice Brothers use old-fashioned instruments—fiddle, accordion, and washboard—to stitch stately folk, rambunctious barroom stomps, and old-time mountain music into something that echoes a dozen or more strains of American music from the early 20th century without replicating any of it. But their relative inexperience with their instruments—“I didn’t start playing the accordion until I was, like, 21, but when I did I wish I’d started a lot earlier—the sound it produces is just beautiful,” Felice says—frees them from the rigid formal traditions of the music they’re picking up and playing with. What they’ve conjured up is a sort of imaginary folk music, a democratic convergence of black and white and urban and rural traditions, that Dylan and the Band produced in the shadow of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music.

“It just sort of came out that way,” Felice says. “We weren’t going for anything in particular. We love roots music, and the music we play sounds like that. ... What’s funny is I’ve never listened to The Basement Tapes.”

The mood of Ian Felice’s lyrics is often morose—the narrator of “Penn Station” seems to sing his tale from beyond the grave, and the underworld characters in the Cajun-flavored “Run Chicken Run” are very clearly headed for bad ends—but those songs are two of the rollicking highlights of Yonder Is the Clock. The band injects them with a desperate, shambling energy that threatens to careen out of control, and the wry point of view saves them from standard-issue sepia-toned romanticism.

“I guess it’s a downer album,” he adds. “But it has some beautiful moments. That’s my brother Ian—he writes most of the songs, and he definitely has a good sense of humor.”